Online Simulations Drive Innovation

Dakota Davis wails in pain as her mother sits anxiously beside her emergency room bed. Dakota is wearing sunglasses.

"The lights are just hurting my eyes so much," groans Dakota, a 17-year-old college student, to her nurse. "I can't even keep my eyes open."

The nurse crosses the room and dims the lights, reassuring Dakota, then continues her assessment. She's taken the patient’s vital signs, asked her to rate the pain of her headache, and carefully felt a rash on her chest.

Then the nurse looks up at a camera that's live streaming the scene.

"Why don't we have a huddle," she says. "You all decide what else I need to assess for."

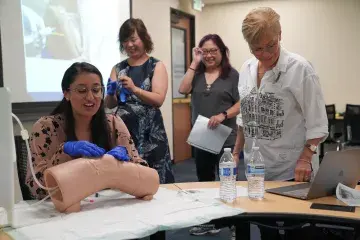

The nurse, in fact, is Professor Velinda Chapman, who is acting out a simulation scenario for an Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing (ABSN) pediatrics class. She is in one of Samuel Merritt University’s Oakland campus simulation rooms, designed to look and feel like a hospital room. The students are watching from home via WebEx. And Dakota and her mother? They’re manikins set up in the simulation room, voiced remotely by another SMU professor.

The huddle is key

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, SMU’s simulation classes have gone virtual. And the online format has prompted Chapman to incorporate an innovative new technique into her simulations: the huddle.

In normal times, a handful of students meet in-person in the simulation room to assess and care for “patients”—typically either actors or manikins. The scenario lasts about 15 minutes, and at the end there’s a group discussion. These days, because only Chapman can be in the simulation room, she’s taken on the caretaker role. At certain key moments during a scenario, she calls a huddle to allow the students watching on WebEx to discuss next steps and instruct her on what to do.

“It’s reflection in action,” Chapman says. “The huddles give them periods to interact and get feedback immediately.”

Students take the reigns

From their homes, eight ABSN students watch the scene with Dakota unfold. When Chapman calls the huddle, it’s their turn to jump into action. The students have a sense of what may be wrong with the patient, because to start the simulation the group spent a few minutes discussing the disease meningitis with Chapman and other facilitators.

The students suggest more questions to ask the patient: When did the rash first appear? Has there been any outbreak of illness in Dakota’s dorm? Has she shared any food or drinks with anyone else?

After a few minutes of discussion, Chapman returns to her role as Dakota’s nurse and the simulation continues, with the nurse incorporating the students’ suggestions.

More huddles, more learning

Chapman thinks the new huddle-focused simulation training could foster better learning in some scenarios than how they’ve been traditionally done—with a group discussion at the end.

“With multiple huddles, there are a lot of opportunities to speak and learn throughout the simulation, rather than just during the final debriefing,” Chapman says.

Chapman got the idea to incorporate planned huddles from a program run by the American Hospital Association called TeamSTEPPS, which is already part of SMU’s curriculum and a proven method of training people to work in teams. She plans on continuing to use the huddle method in select simulations and is already gathering data on its efficacy.

A new kind of simulation experience

For student Dominique Greene, ABSN ’20, it was helpful to have a new kind of simulation experience. Previously, she’d already participated in several in-person simulations.

“There were definitely times where I missed certain signs and symptoms,” she says. “During the huddles, Velinda did a great job leading us to the answer by helping us think critically about the situation and discover what we may have missed.”

Indeed, the regular online huddles actually helped solidify learning in the moment, Greene says.

“We got a different perspective of care by watching someone give care, rather than actually giving care ourselves,” she says. “We were able to look at our skills and what we know in a different headspace.”