When the Healthcare System Failed Her Cousin, She Decided to Change It

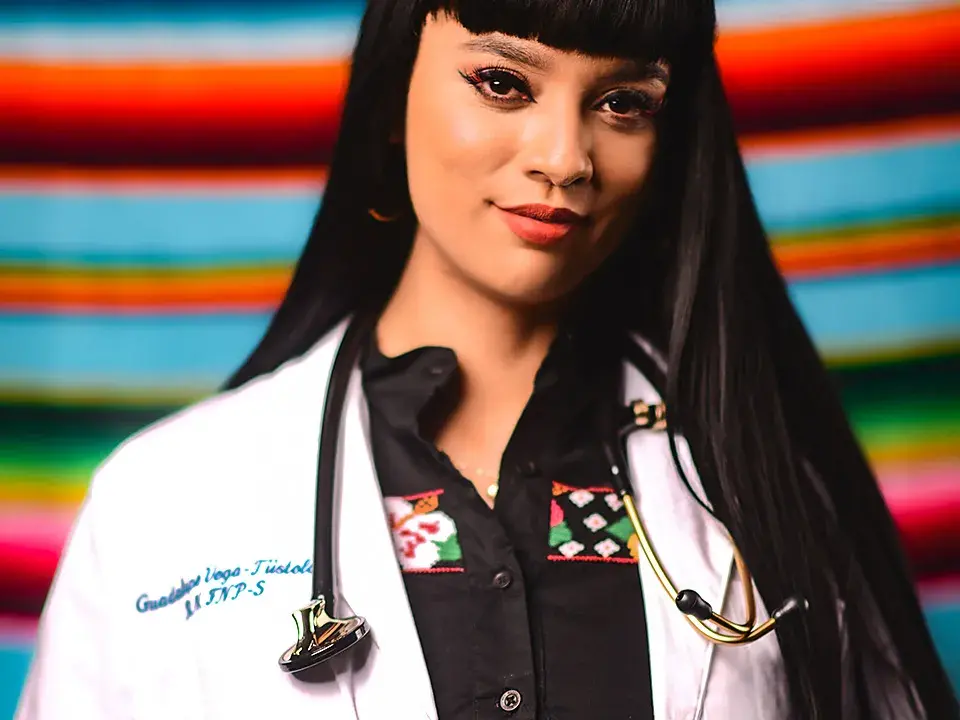

In a photo on her Instagram feed, Guadalupe Vega-Tiistola stands in front of a brightly striped serape, a traditional cloak from Mexico, proudly wearing her new white lab coat that marks her induction as an advanced practice nursing student.

“Here's to seeing more of us in healthcare and helping the communities that helped raise us,” her caption reads.

Guadalupe is two and a half years into SMU’s Entry-Level Master of Science in Nursing—Family Nurse Practitioner (ELMSN-FNP) program. She has been documenting highlights on Instagram that include photos of her stethoscope, fellow students, a manikin, an infant simulator she trained with during pediatrics rotation, her membership into the Sigma Theta Tau International Society of Nursing, and a video of her 12-year-old chinchilla, Bijoux, nibbling on the corner of her homework.

She uses #SMU and #samuelmerrittuniversity and #nursingschool hashtags to offer a glimpse into life as a nursing student and, hopefully, to inspire other people like her, more brown women, more first-generation immigrants, and more Spanish speakers to enter the healthcare field.

Born in Michoacán and raised in Stockton, California, Guadalupe, like a lot of immigrant kids, grew up playing the role of interpreter for her family at doctor’s appointments because there were so few practitioners who could speak Spanish. It was often a disheartening experience, filled with confusion, miscommunication, and, what seemed to Guadalupe, at least, a lack of concern and empathy by many caregivers. When she was 14, her 16-year-old cousin died from a misdiagnosis. Guadalupe’s mother had taken him to a clinic to ask about the inexplicable swelling and bruises all over his body, and he was sent home with little more than a chuckle and a light punch on the shoulder, as if there were nothing to worry about. A couple of weeks later he was rushed to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with leukemia, brain tumors, and no future to speak of.

“We had to make the long, hard decision to let him go,” Guadalupe says, the emotion catching in her throat.

Physical therapy or nursing

Perhaps surprisingly, the experience instilled in her a strong aversion for hospitals, but also a deep respect for nurses and a firm commitment to enter the healthcare field.

“The doctors came and went, but the nurses were the ones who stayed and encouraged us to hold (my cousin’s) hand and talk to him,” she says. “The nurses were the ones who brought humanity back into this horrible tragic experience.”

Guadalupe knew she wanted to do for others what the nurses had done for her family, but in the days and years following her cousin’s death, the smells and sounds in hospitals continued to bring strong, difficult memories to the surface. In college, she majored in kinesiology with plans to become a physical therapist so she could care for patients outside of hospitals, but she eventually heeded the call of nursing. Clinical rotations through the ELMSN-FNP program have helped her work through some of her feelings around hospitals, although her ICU rotation was a “little bit traumatic,” she says. In the future, she plans to work in outpatient community clinics, not so much to avoid hospitals, but to be an earlier point of contact for Spanish-speaking patients.

SMU is playing a key role in helping her get there, not just through the curriculum but through the diversity of its population, including students and faculty. Her peers help her get through each day, and the faculty push her to believe in tomorrow’s possibilities.

“I love having Latino and Black educators because I see myself in them,” she says. “And speaking to them when they’re first gen as well, it’s awesome to know people I can relate to in such high places. I aspire to be like that for someone else in the future.”