Students Detect Heart Defects

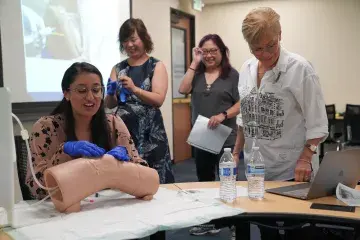

Olena Khudiakova ABSN ’20 has logged dozens of hours reading textbooks and treating mannequin “patients” in SMU simulation labs. But what she has come to value most in the last few months of the Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing program are opportunities to practice her skills on real humans.

Take electrocardiograms (ECGs), for example. They’re a common tool for measuring the heart’s electrical activity to ensure it is functioning properly. During lectures, readings, and demonstrations at SMU’s Sacramento campus, Khudiakova learned how to correctly place ECG electrodes on a patient’s chest and limbs, as well as the machine’s basic readings—including what “normal” looks like or what a skipped heartbeat looks like. But she hadn’t yet practiced on a person.

So, when the opportunity to use ECGs at a daylong, heart screening event for teens (before COVID-19) came up—one of many community health events put on by the University and its nonprofit health partners throughout the year—Khudiakova and others in her program jumped at it.

“Nothing can replace a living patient,” she says.

The students woke before dawn to drive 80 miles to the College of San Mateo, where the event took place. They were among about 50 future nurses from Northern California schools who volunteered their time.

It was a bonus that the patients were teens, Khudiakova says. The screenings often end up alerting families to possible heart irregularities or defects, allowing them to follow up with their family physicians before a crisis.

Such screenings can be rare for teens because insurance carriers typically won’t cover costs unless a patient shows symptoms of heart problems, says Liz Lazar-Johnson, executive director of the San Francisco-based Via Heart Project, which convened the event. Unfortunately, cardiac arrest is sometimes the first symptom, Lazar-Johnson says. In some instances, it’s too late and the youth dies.

“Looks good on a student resumé”

Since Via launched the event in 2015, about 5,760 young people have been screened. Of those, 58 youths were discovered to have previously undetected heart defects and be at risk for cardiac arrest, Lazar-Johnson says.

The 15 or so youths Khudiakova worked with were “all great patients,” she says. “None of them were scared, which made me gain more confidence in what I was doing. It was very helpful to see each of their faces when we explained the process.”

It also was helpful to work with volunteers from other nursing schools rather than her classmates because it forced her to pay closer attention, she says. In between patients, her group discussed what they believed went well and what they wanted to refine during the next screening.

Volunteer cardiologists supervised each group’s care and offered pointers.

“Hands-on ECG experience looks very good on a student resumé,” Lazar-Johnson says. “We greatly appreciate their help at our screenings. And, we want them to advance their learning. No matter how many or how few patients the students work with, it all supports their education, especially because they’re working with teens.”