Runway to the Real World

Natalie Lucas, ELMSN-FNP ’21, is video conferencing with a 14-year-old female patient. Pre-COVID, Lucas would have been in an exam room with the teen at Oakland’s Roots Community Health Center, but these aren’t normal times. Telemedicine is how many healthcare providers see patients these days.

Lucas, a student in the Entry-Level Master of Science in Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (ELMSN-FNP) program, asks the teen what kinds of food she eats.

“For breakfast, usually oatmeal,” the girl responds. “My mom’s cooking for lunch and dinner: chicken soup, squash, carrots. It’s pretty healthy.”

“And how much water are you drinking? What about soda and juice?”

“I drink a lot of water, and peach or guava juice a few times a week,” the girl says.

“You might consider cutting back on the juice because it’s high in sugar,” Lucas says. “I usually tell patients to cut their juice in half. Instead of drinking your second cup of juice, drink a cup of water instead.”

Next, Lucas asks about exercise, and whether the teen has any concerns of her own.

It’s a standard child wellness checkup—almost.

In the room with Lucas, but off camera, is an SMU classmate who interviewed the teen’s younger brother earlier. Assistant Professor Shelitha Campbell is also behind the scenes listening. There’s a Spanish translator on the call to help the children’s mother, as well.

That morning, Campbell met with the students to prepare them for the child wellness exams. If they got stuck or forgot something, she’d be there for support. Campbell is the faculty practice clinician at Roots, which means she sees patients and is able to bring students in to shadow her and see patients under her supervision.

“Faculty Practice Clinics (FPCs) are different from traditional rotations in that we, the faculty, are right there with students,” says Assistant Professor Catherine Tanner, a colleague of Campbell’s who is a faculty practice clinician at Marina Village Medicine, a primary care clinic in Alameda. “We know the curriculum and the expectations for the students that semester. So, students really get to work closely with faculty on developing their clinical skills and applying what they’re learning in class.”

FPCs are one of the things that set SMU apart. Fewer than half the nursing schools in California use them.

Moving into sensitive territory

Roots is one of six FPCs where SMU students work alongside faculty seeing real patients in clinical environments. The program started with ELMSN-FNP students but has expanded to include prelicensure RNs, such as BSN students, and Entry-Level Master of Science in Nursing – Case Management (ELMSN-CM) students. Like traditional clinical rotations in a hospital or doctor’s office, students learn by shadowing and seeing patients. But unlike traditional clinical rotations, they have faculty closely supporting and guiding them and benefit from more time to see patients, make assessments, and ask questions.

In addition to Roots, SMU has FPC partnerships with West Oakland Health Center, Brighter Beginnings, Axis Community Health, and Marina Village Medicine in the Bay Area, as well as with Elica Health Centers in Sacramento.

Tanner calls the FPCs “structured learning environments.” “We don’t always have the same time pressures,” says Tanner. “Typically, at other clinical sites, you might be seeing 18 to 20 patients in a day. But we tend to start our students with about 10 a day and then ramp it up as students’ comfort and competency increase.”

Lucas, who is still online with the 14-year-old female patient, is finishing her preliminary questions and moving into more sensitive territory. Lucas wants to ask her about any potential sexual activity, to gauge whether there are any sexual health and wellness issues that might need to be addressed.

Typically, Lucas would ask the girl’s mother and anyone else to step out of the room for privacy. But the virtual situation is more complicated. Though she’s requested privacy, Lucas can’t be sure who is still listening. She starts by asking about whether the teen has friends who are dating and slowly focuses the questions on the girl herself. The teen seems hesitant and answers somewhat evasively.

Campbell, who is observing the interaction and wants to be sensitive to the teen’s privacy, scribbles on a whiteboard: “Follow up later?”

Lucas nods in acknowledgment. “Maybe we can chat more about this later? We have a follow-up scheduled for next month. Would that work?” Lucas asks the teen.

The patient agrees. Maybe next time she’ll know what to expect and feel more comfortable. Rather than intervene in the call, Campbell was able to help Lucas make her own way through it. That’s exactly the sort of scenario the FPCs are set up for.

“I see myself working in a community health setting like Roots one day,” says Lucas, who is transitioning into nursing from a 25-year career in pharmaceutical sales. “One of the primary reasons that I pursued the nurse practitioner route was to serve in a capacity to address chronic health issues that impact vulnerable communities. At this point in my life, doing something to give back to the community I live in is really significant to me.”

Fearful look

On a warm Friday afternoon in February, six students are in the parking lot at Elica Health Center in Sacramento, providing COVID-19 vaccines. The nonprofit’s three mobile units provide everything from COVID-19 tests and vaccinations to high school sports physicals and “street medicine” for the homeless in Sacramento and Yolo counties. Students say the mobile units feel more dynamic because they go to where the need is in all kinds of communities.

In the parking lot, under a large canopy, a homeless man in his late 50s sits on a metal folding chair. He looks up fearfully at Entry-Level Master of Science in Nursing - Case Management (ELMSN-CM) student Gabriel Winn, ELMSN-CM ’22, and Marin Gibson, ELMSN-FNP ’23, who stands beside him about to give the man his first vaccine shot.

“Am I going to die?” the man asks, clearly having second thoughts about agreeing to have the vaccine.

Faculty instructor Nicole Love comes over to listen to the conversation.

“Dying from the vaccine is something people are worried about, but it’s a rumor,” Winn tells the man in a calm voice. The students explain that the virus is far more dangerous than the vaccine, putting the man at ease enough that he again agrees to the shot.

“I was trying to mirror the emotion I wanted the patient to feel,” Winn later recalls.

Afterward, Love pulls the students aside to talk about what went well and what they might improve on next time. For example, instead of standing, they could sit with the man to be more on his level and help him feel more at ease, she suggests.

The son of a preacher, Winn would like to continue working with the homeless population in some capacity in the future. He says being there for others is in his blood. “Elica has reminded me of the core principles I was taught ‘helping those who don’t have,’” he says. “I’d like to see how I might work that into my career.”

For student Ghada Saloha, ELMSN-FNP ’21, working with the mobile units also brought a welcome variety of experience and circumstances.

“We learn how to educate and treat all types of patients and to help them navigate their circumstances and enhance their quality of life. As a result, I’m much more comfortable promoting health in many types of settings, like at a school or on the street,” she says.

144,000 hours

At Marina Village in Alameda, where Professor Tanner is an FPC clinician, students experience what it’s like to work at a small, private primary care facility, with one doctor and two nurse practitioners. Most patients are older than 55, giving students an opportunity to work with an aging population, including many on a fixed income.

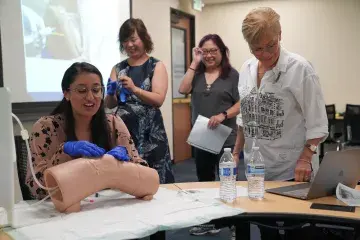

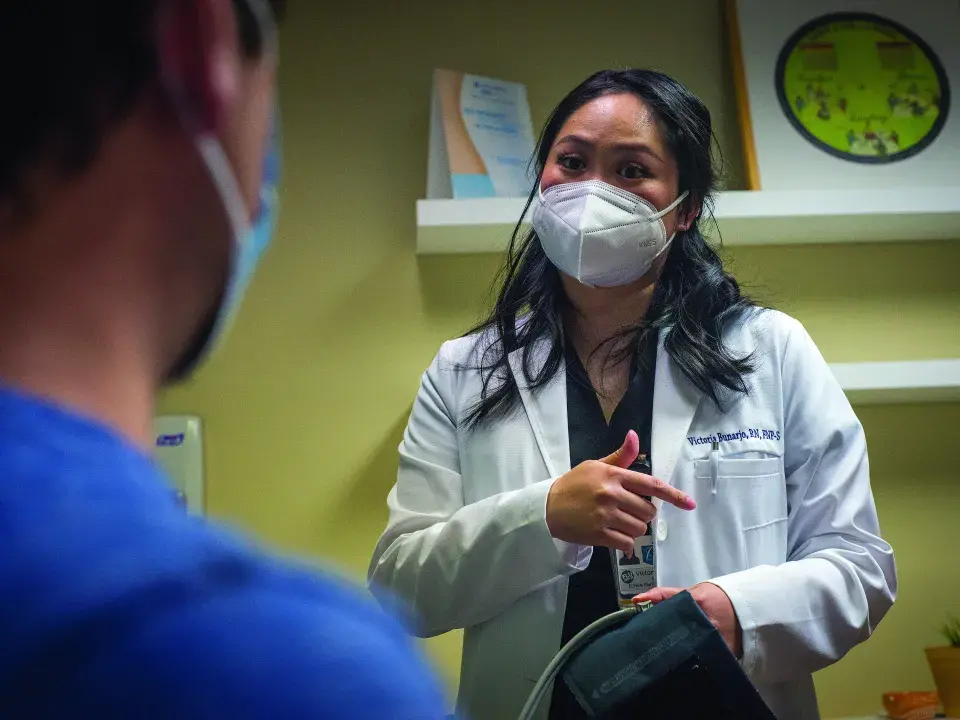

Student Victoria Bunarjo, ELMSN-FNP ’21, spent time the prior night reviewing the lab results and charts of the patients she’s seeing today. One, a 65-year-old female, has a follow-up to see how her blood pressure is doing. From her chart, Bunarjo knows the patient is diabetic and that her kidney function is impaired. She wants to put the patient on diabetes medication, 500 mgs of Metformin twice a day, and to work with her on a dietary plan. In the morning, before patients start to arrive, she consults with Tanner. There could be some gastrointestinal side effects, Tanner reminds her, so it’d be best to start at once a day and then evaluate. With an agreed course of action, Bunarjo sees the woman alone later that day.

“This is a safe and comfortable environment for the students to think through their patient plans,” says Tanner, who has been seeing patients with students at Marina Village for nearly four years. “I give the students a moderate amount of autonomy,” says Tanner. “I want them to be able to create their own persona as a clinician.”

In some traditional clinical rotations, Tanner says, students are only allowed to shadow a clinician and not to perform actual work. “That’s not enough,” she says. “They need to be seeing patients, taking medical histories, touching them, and doing exams. They need to be thinking independently and making their own decisions—with the support of faculty.”

Bunarjo, who was a medical scribe before enrolling at SMU, says she enjoys working with an elderly population and wants to work in a private family practice like Marina Village in the future.

“I enjoy family practice because I get to build long-term relationships with patients,” she says. “Over time, I learn about all aspects of their life, and can help them figure out how to make adjustments for their wellness.”

Since SMU started FPCs in 2008, over 300 students have participated. That’s an estimated 144,000 hours spent caring for community patients over the years.

“On average an FNP student will complete anywhere from 330 to over 630 hours caring for community partner patients,” says Tanner. “Because of this commitment and the high quality of care, some of SMU’s community partners like Roots, Elica, and Marina Village have expanded to include SMU students from ELMSN-CM and pre-licensure RNs into their community clinic settings.”

Faculty contribute even more, spending between nine and 18 hours a week seeing and managing community patients.

For case management student Saloha, the Elica mobile clinic was a transformative experience. “Our amazing faculty were always so supportive and knew the fine line between guiding us and letting us work independently,” she says. “That gave us a profound level of confidence.”

The dream, says Tanner, is for SMU to one day have its own community clinic that all students can contribute to. But for now, faculty stay on the lookout to expand existing partnerships or create new ones.

“The more hands-on learning opportunities for students, the better,” Tanner says.