After His Mother Was Injured, Pablo Tavares Saw a Need for Better Physical Therapists

As a child, Pablo Tavares, DPT ’20, was a regular companion to his mother’s appointments, translating her Spanish to health care providers. At 12, he accompanied her to a physical therapy appointment for an overuse injury on her right hand that she’d picked up from packing lettuce at a plant in Salinas.

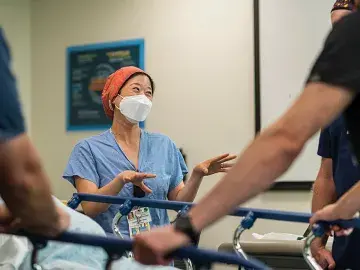

He watched as the therapist used iontophoresis, a usually painless technique that uses an electric current to deliver medicine through the skin. But something went wrong and burned his mother. She never returned to physical therapy. For months, she couldn’t grip well until the burn healed. She still has a scar today.

Two years later, Tavares’ soccer coach suggested he see a physical therapist for pain in his knee. Tavares hesitated, still harboring negative feelings about his mother’s experience. Eager to play soccer pain-free again, however, he reached out to a physical therapist and told him about his mother’s experience. “Don’t worry,” the therapist assured Tavares, “we won’t burn you.”

Indeed, Tavares wasn’t burned, and several weeks of therapy not only rid Tavares’ of his knee pain but it sparked a vision for his future.

“My therapist was great, a good communicator, a good instructor and teacher,” Tavares said. “I actually saw what a good physical therapist can do, what they can provide to someone, and I thought, ‘You know what? I can do that and I can do it better than those people that treated my mom.’ After that, I was set on what I wanted to do.”

That was at age 12. Now 26, Tavares will graduate from the Doctor of Physical Therapy program in May.

Get to know the person behind the patient

After earning a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology from San Jose State University, Tavares was drawn to Samuel Merritt University because of its smaller class sizes, individual attention from accomplished faculty, and its sense of inclusiveness.

“There’s this culture of being inclusive and appreciating people’s cultural differences and backgrounds and that’s something that’s often overlooked at other schools,” Tavares said. “At Samuel Merritt, it’s pretty much front and center.”

That inclusive approach, he said, extends not only to the campus culture but also to the way students are taught to interact with patients in clinical settings. Professors explicitly teach students to understand how their own cultural backgrounds and that of their patients can impact care, Tavares said.

“When I first started PT school, I didn’t really pay attention to this type of stuff,” Tavares said, referring to the bedside-manner techniques he’s been trained in at SMU. “The skills are not the hard part, it’s putting it all together and understanding your patient’s story, what they’re trying to tell you, understanding their perspectives. That is by far the hardest part and something that unfortunately a lot of PTs don’t do.”

Do you trust me?

Tavares has put that approach into practice in Bay Area clinicals where he has often been the only native Spanish speaker. It’s allowed him to handled full initial evaluations in Spanish without the need for a translator. When Spanish-speaking patients come in, they are often placed on his schedule and he’s assisted other therapists and nurses with Spanish-speaking patients.

“I asked one of my patients if it put her at ease knowing I could speak directly in Spanish,” Tavares said. “She said it’s a reassurance thing, she said it’s hard to put your trust in someone when you can’t communicate with them.”

After graduation, Tavares plans to stay in the Bay Area and focus on orthopedic physical therapy. Longer-term, he envisions returning to his hometown of Salinas, where physical therapists are in shorter supply as is the case in many rural areas. There, Tavares said, he’d like to start an injury prevention program for all types of manual-labor workers, including plant workers like his mother and field workers like his father, who is now retired.